The Minutes of the Hildegard von Bingen Society for Gardening Companions

with Sophie Seita

We announce the unusual and unprecedented discovery of a secret society of women, that we believe to have been founded by Hildegard of Bingen, and centred on the sharing of knowledge of gardening, music, and collective making.

We invite you, readers, to join us in our investigations: do you know historical women for whom the bonds of female love and anchored roots were so strong that they, too, may have been taking part in the quest to preserve and pass on Hildegard’s musical, mystical knowledge of the gardens? Please do not hesitate to get in touch with us to share any information you might have that would assist in our investigations. As so little information about this collective is written, we are relying on stories, gossip, and hearsay. If any of these have been passed down to you, we are all ears (and as Suzanne Cusick writes, 'what if ears are sex organs?').

Also, in order to pursue research into the activities of the society in the absence of historical evidence, we propose to revive and reenact its founding, to live it again as a form of scholarship, singing, and knowledge creation. We invite you to join us, through communal activities of tending, sowing, mending, mixing, teaching, learning, making, singing, weeping. We will share the knowledge and healing of the gardens through our care towards each other. JOIN US ON INSTAGRAM + BY ADDING YOUR NAME BELOW.

Also, in order to pursue research into the activities of the society in the absence of historical evidence, we propose to revive and reenact its founding, to live it again as a form of scholarship, singing, and knowledge creation. We invite you to join us, through communal activities of tending, sowing, mending, mixing, teaching, learning, making, singing, weeping. We will share the knowledge and healing of the gardens through our care towards each other. JOIN US ON INSTAGRAM + BY ADDING YOUR NAME BELOW.

on the discovery of the societyI spent my time investigating insects. At the beginning, I started with silk worms in my home town of Frankfurt. I realized that other caterpillars produced beautiful butterflies or moths, and that silkworms did the same. This led me to collect all the caterpillars I could find in order to see how they changed.

These are the words of Maria Sybilla Merian, seventeenth-century scientific naturalist and botanic illustrator, renowned not only for the quality and realism of her drawings, but also for being a woman at a time in which the purview of scientific research was exclusive to men. I was first introduced to her through a spiral of footnotes, and quickly found myself caught in a web, anxious to collect and know more. Quickly, I shared my collections and discoveries with my colleague X—under strict instructions to guard our discoveries carefully, as they might prove to be dangerous. Together, we began to assemble a compendium of women gardeners, with alluringly and alarmingly similar traits. Women who—like Merian—shunned the company of men in order to run the only all-female scientific illustration workshop in Europe. Women, who—like the gardener and artist Mary Delany, were vocal about the value of female friendship and its superiority to marriage. Women who—like the Chinese poet, courtesan, and botanist Xue Susu—devoted themselves to supporting and travelling with their female companions. Our collection of caterpillars, so to speak, led us to scour archives, devour diaries, hour by hour coming closer to an eventual realisation. These women had something in common beyond their surface level similarities. Eventually, we found what we did not even know we were looking for: a book, containing scrawled numbers and initials in an unfamiliar script, between drawings of plants and music notes. We leapt to the only possible conclusion: here lay before us a record of the secret society founded by Hildegard von Bingen at Eibingen Abbey around 1169. The only reference to the founding of this fellowship is in her text, Lingua Ignota per simplicem hominem Hildegardem prolata, in which she describes the vox inauditae linguae she had been developing, a secret unknown language, which was designed to pass on ‘divine knowledge for the future’. It has been assumed until now by all scholars that there were no initiates of the language to pass on the knowledge it could convey, and that her dream of a society of women who might carry on her legacy and mystical botany vanished with her death in 1179. However, we now believe that a whisper network of women carried on this language and knowledge, mostly orally, under the guise of gardening together, living together, praying together, writing together, and especially, singing together. The peak of the society appears to have been in the 19th century, when we are confident a group of women met regularly in the home of Madame de Stael under the auspices of her Parisian salon. The book that we obtained suggests a resurgence of the group also in St. Ives, meeting in the Sculpture Garden of Barbara Hepworth, likely brought from a collective in South Africa into which the composer Priaulx Rainier had been inducted. We refer to this society as The Hildegard von Bingen Society of Gardening Companions, though we believe it has also at various times operated under other names, including The Hildegard von Bingen Society for the Preservation and Perpetuation of Women Gardeners, Hildegard’s Starlets, Sorceresses, Sapphists, and Llamas, and likely many others. Yet, from there, our trail runs cold. These women’s collective work was often secretive by nature, because of the difficulties of being a woman in such male-dominated fields of the natural sciences. Individual women occasionally withstood the conventions of society and made their names in the field, but only through the guise of poetry, art, music—acceptable women’s work. The absence of documentation about the activities, membership, and creative work of this society makes it difficult to present our findings in the usual scholarly channels, or to authenticate them by conventional historical means. We believe, however, that Hildegard’s eventual intention was for the legacy of the society to become public and widespread, for the vox inauditae linguae to become heard. As such, we are actively, insouciantly, eagerly pursuing our research with the ardent fervor of a germinating seed, an erupting cocoon. |

Submission from an Anonymous Reader

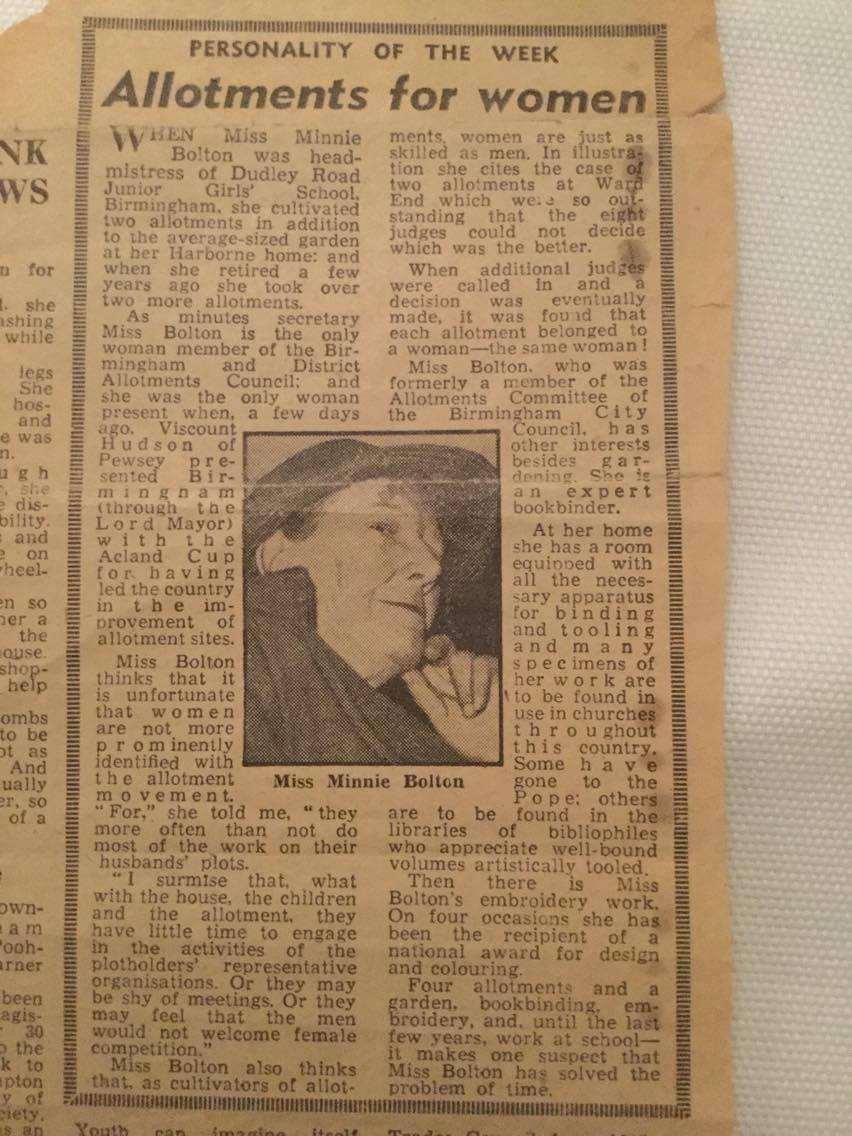

My first knowledge of the society was due to a chance encounter in my own family archives. While exploring old photographs at the home of my cousin X, I found a newspaper clipping featuring my great-aunt Minnie. Minnie was a legend in my family, a fierce and feisty woman who never married, but was an avid reader, diarist, and bookbinder, as well as an especially talented and devoted gardener. The clipping documents her advocacy—as the sole female member of the Birmingham and District Allotments Council—on behalf of women gardeners, and desire for more women to become involved in the allotment movement. Her cap and curious expression intrigued me, and I asked my cousin if he knew more about her role in the allotment society. He could not find any documentary evidence, but had heard a rumour that following the publication of this story, Minnie had begun to assemble a group of women gardeners regularly, and that it had, in fact, been her goal to create some kind of women’s allotment society. Could she, too, have been carrying on the legacy of Hildegard’s companions? |